A snapshot of my indigenous heritage in Lake Toba, Tapanuli, Sumatra.

Photo: Siska Sihombing

Photo: Siska Sihombing

A Batak indigenous woman is planting crops in her field near my father’s village. We chat. The lady, who happens to be a distant aunt, has lived in the Tapanuli region with her extended family near the world’s largest super-volcanic lake, Toba, all her life. Indeed, her people have tilled these lands even before the beginning of the first arrival of the Batak people thousands of years ago. To date, our recorded clan and family trees are headed to the 18th generation. We talk about the changing climate. The sun has been relentless this year, and the crop cycle is really disturbed, waiting for the rains…

Photo: Siska Sihombing

Photo: Siska Sihombing

Batak women have extensive knowledge about local flora and fauna and rely on traditional farming methods. They play significant roles in the conservation and preservation of biodiversity. Their contributions are deeply intertwined with their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and the socio-economic fabric of their communities. This includes understanding the medicinal properties of plants, sustainable harvesting methods, and the seasonal patterns of wildlife. For example, I remember my mother explaining sap-tapping to me, how we should carefully collect the sap with bare hands so the trees will be preserved and the sap can be collected regularly, a method in Batak known as maragat. Such knowledge is crucial for the sustainable use and conservation of local biodiversity.

Every visit back to my homeland, I am struck by the resilience and adaptability of our people to the changes brought by the outside world, but also the fragility of our land and culture to the challenges that we are facing.

Photo: kompasiana.com

Photo: kompasiana.com

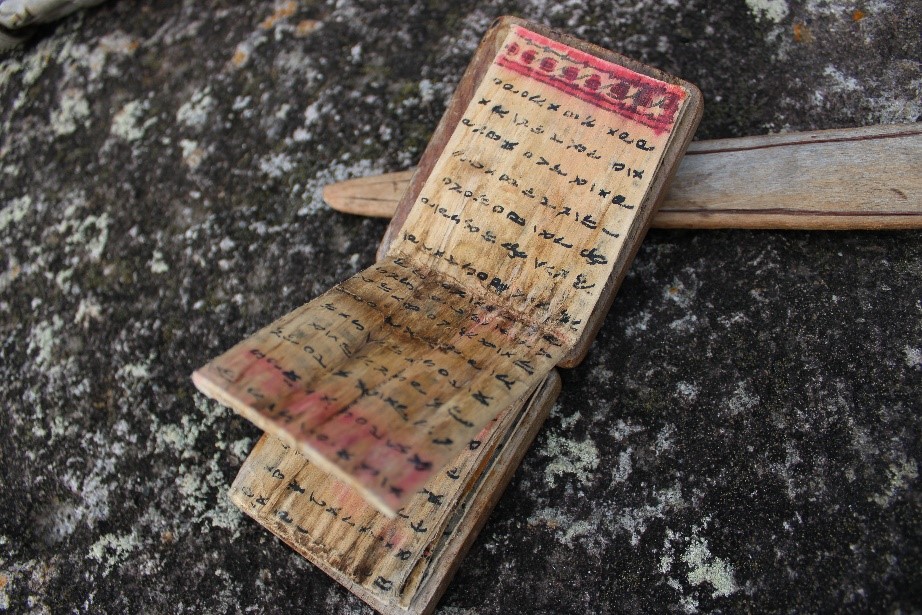

Long reputed as very resistant and defensive people in the records of Islamic geographers, Chinese merchants, and even Marco Polo, who stayed on Sumatra for five months waiting for the trade winds to return to Europe, the Batak peoples eluded colonial assimilation and missionary influence until the mid-19th Century.

However, for the Toba Batak, it was only in 1890 that my people were “discovered” by the external world. An Italian researcher and adventurer, Dr Elio Modigliani, was the first to engage with our culture and navigate through the Toba Batak lands, then considered hostile and inaccessible to Europeans. This was after more than 300 years of Dutch East India Company (VOC) colonisation in the Indonesian territories. He used his diplomacy to gain the trust of a local chief who guided him past the Dutch authorities and secretly into the highland region. His travels included visiting places like Lake Toba, where he observed its unique geographical and ecological characteristics, and his diaries express his awe at the first site of the lake’s spectacular waterfalls.

Unfortunately, the VOC, spurred by missionary spies, finally imposed their rule on the Batak, killing the famous warrior leader Si Singamaraja XII and his family in 1904 and murdering many innocent people, including nearly 2,000 women and children, during a brutal campaign of occupation. However, the Batak people continued to resist and were firmly part of the Indonesian independence struggle from that time until 1954. The Toba Batak are now a recognised ethnic minority culture in Indonesia.

Photo: Siska Sihombing

Photo: Siska Sihombing

Situated in the highlands of Sumatra, Indonesia, Lake Toba’s serene shores accommodate the Toba Batak indigenous community; Batak peoples have thrived, their lives deeply connected with the giant lake’s waters. The narrative of Lake Toba is one of nature and culture, where indigenous wisdom meets the contemporary conservation measures. It is estimated that Lake Toba was created during an explosion around 73,000-75,000 years ago and is the most recent supervolcanic eruption. Our Batak mythology agrees, telling us the lake was created for the Batak people by supernatural forces, and it remains the source and soul of our life and land.

Lake Toba is indeed a region of environmental and cultural significance, and parts of it are protected, but not as a protected area with formal designation by the authorities. The area around Lake Toba has several zones with different levels of protection designed to preserve its unique environment and the cultural heritage of the indigenous Batak people. Efforts have been made to acknowledge the area’s importance for conservation, especially given its significance following its recognition as a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2020. This status aims to protect the area’s geological heritage (one of the largest calderas on earth) while promoting sustainable benefits for biodiversity. The UNESCO Global Geopark network encourages a holistic approach to the area’s natural and cultural features, which aligns with the conservation goals.

As with many such natural areas around the world, conservation efforts are often a balance between protecting the environment and meeting the needs of local communities, as well as developing local economies. The designation of Lake Toba as a Geopark is a step towards more comprehensive recognition of the protection and management needed to ensure the conservation of its unique natural and cultural values.

This largest volcanic lake in the world is home to a unique species of fish known as the Batak fish or Ihan Batak. This species, registered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, also contributes to Lake Toba’s designation as a Key Biodiversity Area. The Ihan Batak is endemic to Lake Toba, meaning it is found nowhere else in the world. The Batak fish are an essential part of the local ecosystem as they are an important indicator of the healthy freshwater in the lake and connected rivers. For important traditional ceremonies, the lakes hold spiritual and cultural significance for the indigenous Batak people.

The conservation of the Batak fish in Lake Toba is not just about preserving a species; it’s about maintaining the ecological balance of a unique ecosystem and respecting the cultural heritage of the Batak people. It requires a multifaceted approach that combines scientific knowledge with community engagement and sustainable practices. Near the Toba Lake, in the Tapanuli Selatan forests, lives the recently-described Tapanuli Orangutan, a critically endangered species fragile to logging, mining and plantation concessions in their habitat.

Photo: WWF DE

Photo: WWF DE

The Batak’s spiritual bond with Lake Toba shapes their conservation efforts. Their traditional ecological knowledge is a compendium of insights on environmental stewardship. Their living library, detailing the ecological rhythms of Toba, could align with the global standard for area-based conservation, such as the IUCN Green List Standard criteria for inclusive governance and ecological representation. The Standard recognised the involvement of indigenous peoples in conservation, recognising their role as primary guardians of biodiversity.

However, the issues of modernity and industry present issues over Lake Toba. Palm oil plantation, logging, timbers, mining and non-sustainable tourism practices are the real dangers. The environmental degradation risks undermining the Batak’s way of life and the lake’s ecological integrity.

This tension calls for a reminder of the promotion of traditional conservation methods. More structured frameworks like the recognition of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) guided by the IUCN Green List Standard for fair and effective conserved areas could be a solution to foster resilient ecosystems.

Yayasan Danau Toba is one NGO working tirelessly to protect and conserve Lake Toba. They strive to promote sustainable development and protect Lake Toba’s unique biodiversity and cultural heritage. From the “50 Indigenous Leaders’ Voices Indonesia” report in 2023, Jonter Simbolon, a customary leader from Samosir Island of Lake Toba, indicated that the community hopes for governmental recognition and reclassification of their customary lands so they are not considered state forest areas. This would enable them to continue protecting their forests and traditional areas.

The central government has advised district governments to recognise these customary lands, indicating a potential shift towards formal acknowledgement and support for the community’s conservation efforts.

Countries are collaboratively working to ensure that by 2030, at least 30% of global areas of importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions are effectively conserved and equitably governed systems, including recognising indigenous and traditional territories (30x30). The CBD Decision 14/8 defines OECMs as areas that achieve long-term and effective in-situ biodiversity conservation outside of protected areas. The current efforts are geared towards preserving biodiversity and spiritual-cultural heritage through collaborative and inclusive conservation models that might fit the Toba Lake to be recognised as OECMs, in addition to the Geopark status.

Photo: Wikipedia

Photo: Wikipedia

Lake Toba’s waves resonate far beyond its waters, serving as a global testament to the importance of integrating indigenous knowledge and perspectives with global conservation efforts. The Toba Batak’s ecological practices and spiritual paradigms show the traditional approach immensely. This demonstrates how the traditions, beliefs and cultural practices of the Toba Batak people can help conserve their most precious resource freshwater ecosystem, Lake Toba.

I work for IUCN’s Global Protected and Conserved Areas; I can hopefully bring more support to Batak conservation efforts, but also share our culture, heritage and sustainable practices to the world through the programmatic and projects I engage with and with the many diverse partners and people I meet.

By Siska MC Sihombing