Strengthening conservation and restoration through the Species Threat Abatement and Recovery metric

A new tool – the Species Threat Abatement and Recovery metric – promises to help practitioners assess the potential for conserving threatened biodiversity, and set site scale or landscape scale targets compatible with the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Strategy. This ground-breaking approach is now being applied to forest landscape restoration projects with promising results.

Photo: (c) Boudewijn Huysmans-Unsplash

Throughout the world, nature is declining at rates unprecedented in human history. As many as one million plant and animal species are facing extinction, and the loss of these species threatens the ecosystems and ecosystem services upon which all life depends.

Halting this irreplaceable loss is one of the defining challenges of our time – an effort that will require contributions and changes in behavior from nearly all sectors of the economy and from all people. But what actions should be prioritised and where? Nature’s biodiversity and threats to it are distributed unevenly throughout the world. And similarly, the many conservation and restoration actions put forward to address the species extinction crisis differ with respect to their potential contribution towards conserving threatened biodiversity.

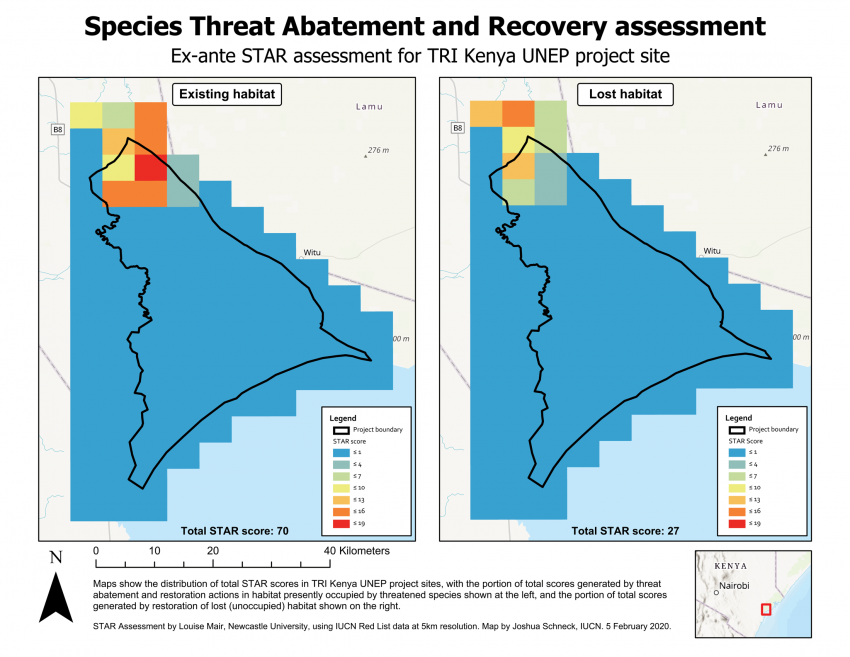

To help make sense of this complexity and help practitioners, investors, and governments compare and prioritise different conservation and restoration actions, IUCN and partners have developed a new methodology and suite of tools. Called the Species Threat Abatement and Recovery (STAR) metric – STAR allows for calculation of a quantitative measure of the benefits to biodiversity from different conservation and restoration actions. And critically, potential impacts can be assessed and compared at any scale, from project-sized landscapes of a few hectares on up to national, regional and global initiatives.

The ground-breaking STAR methodology – a joint collaboration involving some 55 organisations – was recently published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution

Powered by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

Powered by data from IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species – the gold standard for information on threatened species with over 134,400 species assessed to date – STAR identifies which threatened species are found in a landscape, the scope and severity of the threats facing those species, and the kinds of conservation and restoration actions that will most benefit their conservation.

Developing the STAR methodology into a tool for restoration practitioners

For STAR to fulfil its intended impact in helping to address the species extinction crisis, new tools are needed to bring this methodology into the hands of stakeholders. With this in mind, IUCN and partners are piloting an application of STAR to assess degraded landscapes where stakeholders are in the process of designing and implementing a range of conservation and restoration actions.

With support from the Global Environment Facility, STAR assessments are being piloted in four countries participating in The Restoration Initiative – an IUCN-led programme supporting ten African and Asian countries in achieving shared restoration goals. Assessments are being prepared in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Kenya and Myanmar. Results from these assessments will help in understanding not only what kinds of information are most useful, but also how this information can best be presented and communicated to a range of stakeholders including policy makers, investors and conservation practitioners.

Photo: TRI partnership

Photo: TRI partnership

Looking ahead

Another important potential application for STAR is in the development of science-based targets for biodiversity. Just like the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degress celsius in the Paris Climate Accord, STAR will allow for the adoption of similar quantitative, science-based targets for biodiversity conservation. These can include targets for individual countries, individual sectors such as the agriculture and mining sectors, the global community, and more. This potential application of STAR is under consideration as countries that are signatories to the Convention on Biological Diversity deliberate on a new post-2020 strategic framework.

As the world emerges from the worst economic and humanitarian catastrophe since the second world war, the need to identify and prioritise conservation actions and investments that maximise the benefits of scarce resources for biodiversity conservation is even greater. STAR is one promising approach for doing just that.

For more information, please contact Joshua Schneck: joshua.schneck@iucn.org