Reconnecting wildlife habitats - Can Htamanthi Become a Source Site for Tigers?

In the last hundred years, tiger habitat has been significantly fragmented and transformed into isolated patches of habitats. A particular site can hold breeding females and a viable population (source), while a neighbouring one might have been depleted by poaching (sink). The key in this case is to recreate connectivity via corridors to allow the animals from source populations to disperse into sink habitats and to alleviate the damages when a disaster occurs.

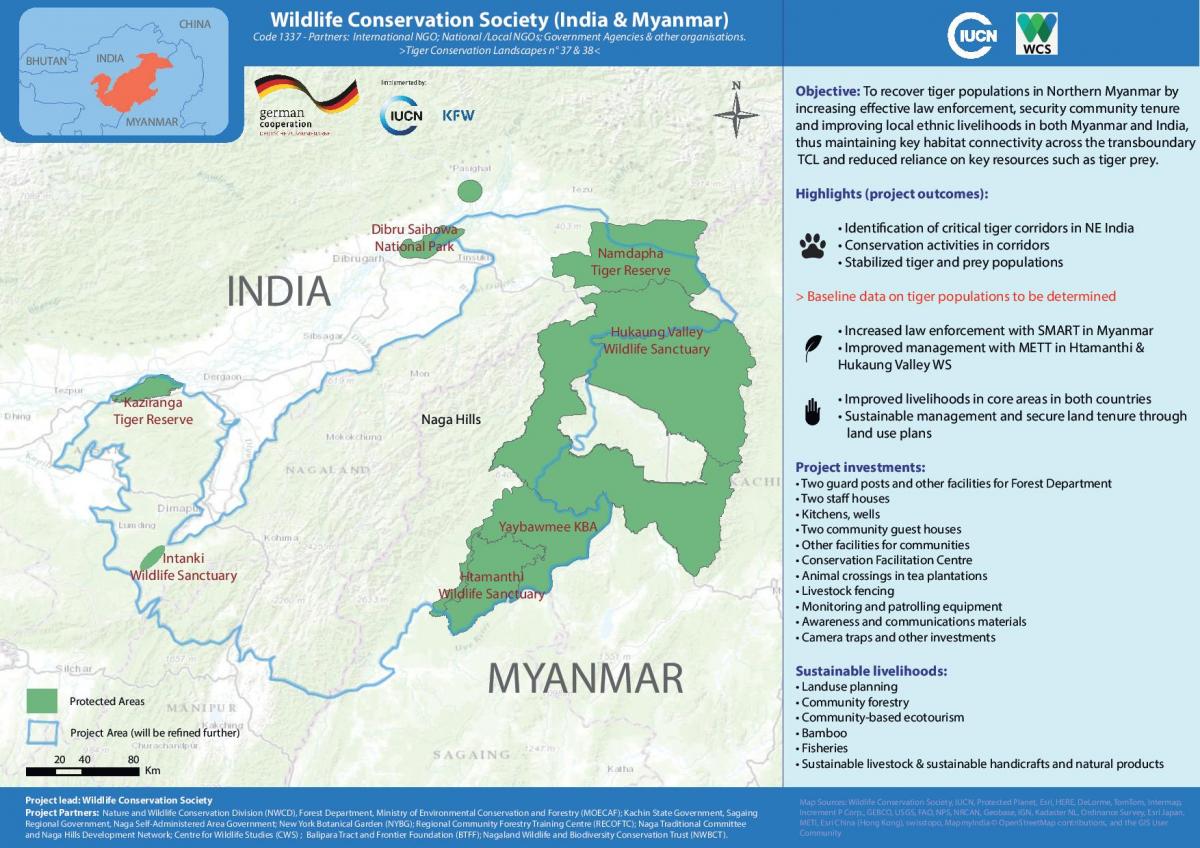

Htamanthi Wildlife Sanctuary (2,151 km2) is roughly 80% closed forest that is semi-evergreen, deciduous, and teak bearing. Like many other tiger sanctuaries, it faces major threats to tiger habitat, prey, and the tigers themselves. However, past and present studies show that there is hope for the cats in this sanctuary.

Myanmar conducted nationwide tiger surveys during 1999-2002. Three sites had confirmed tigers – Hukaung Valley, Htamanthi and Tanintharyi. Another study in the 1990s estimated the Htamanthi population of tigers to be about 15 individuals.

Recent studies in Htamanthi indicated the continued presence of seven Asian wild cats – Tiger, Leopard, Clouded leopard, Golden cat, Marbled cat, Jungle cat, and Leopard cat. This diversity is indicative of a robust ecosystem with a solid prey base of herbivores such as Gaur, Sambar deer, Barking deer, and Eurasian wild pig.

There have been few records of tigers moving across the greater Htamanthi region in recent years. But decades ago, the entire stretch of land was connected, with tigers, elephants and other animals dispersing freely across international borders. Today, limitations to tiger movement between India and Myanmar don’t arise from lack of green cover, but more from small-scale hunting and lack of prey.

Recently, tiger tracks were reported extensively in both the buffer zone and villages surrounding Htamanthi by community engagement teams. In the same period, patrol teams, confirmed the presence of other threatened species throughout the sanctuary. In the core management area, three tigers were captured by the same camera trap (picture above). This suggests that the core area is crucial to the social relationships of these tigers. Other tigers were also recently photographed in Htamanthi.

Htamanthi sits close to the international border close to where there are important tiger landscapes in India. In February 2016, a tiger, dispersing through the community-managed forests of the Nagaland in India, was unfortunately shot by villagers. The first official record of tigers in Nagaland in the past decade, this incident brings to light that there is still movement of tigers through this region. Immediately after the tiger was discovered and photographed, WCS-India worked with the Nagaland State Forest Department and WCS-Myanmar to confirm that this tiger was not one of any of the known tigers of Myanmar.

Following this incident WCS India, its local partner, Nagaland Wildlife and Biodiversity Conservation Trust, and the State Forest Department engaged with local community leaders in Nagaland to emphasize the importance of providing the occasional dispersing tigers with a free pass. And shortly thereafter these communities reported a possible second tiger to the Nagaland State Forest Department and to WCS. Their positive response shows us that, with support from conservationists, Nagaland can serve as a link between resident tiger populations in India, and habitats in Myanmar, such as Htamanthi.

With good conditions for prey and being a manageable size, Htamanthi could host a vital transboundary source population. The success of the site through a source-sink model relies on securing habitat connectivity in the north (Hukaung Valley), the west (Naga Hills), and tiger reserves in India. Future study of potential connectivity for tigers between high-density source populations in India, such as the Kaziranga National Park and habitat in Myanmar, could guide future tiger recovery programmes in Myanmar.

Written by Hla Naing, WCS Myanmar & Divya Vasudev, WCS India