Demystifying the World's Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities

A global movement to restore deforested and degraded forest landscapes is emerging. What should forest landscape restoration achieve? And where should it occur?

By Lars Laestadius, Katie Reytar, Stewart Maginnis and Carole Saint-Laurent

A global movement to restore deforested and degraded forest landscapes is emerging. The global Bonn Challenge, launched in 2011, calls for the restoration of 150 million hectares by 2020. The New York Declaration on Forests, signed in 2014, extended that target to an additional 200 million hectares by 2030. And this past December saw the launch of Initiative 20x20, a program to bring 20 million hectares of degraded land in Latin America under restoration by 2020, much of it in contribution to the Bonn Challenge. Initiative 20x20 is getting close to receiving full commitments to its goal and the Bonn Challenge has seen significant announcements of restoration intent from more than a dozen countries as diverse as the United States and Rwanda.

The movement is gaining momentum, which makes this a good time to clearly define what forest landscape restoration is, what outcomes it should achieve and where it should occur. Here, we demystify the world’s restoration opportunities.

What is forest landscape restoration?

Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) is usually defined as a process to regain ecological integrity and enhance human well-being in deforested or degraded landscapes within biomes with the natural potential to support trees. Importantly, the goal of FLR is to enhance native ecosystem functions. It should bring ecological and economic productivity back without causing any loss or conversion of natural forests, grasslands or other ecosystems. FLR does not call for increasing tree cover beyond what would be ecologically appropriate for a particular location.

What is the Atlas of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities?

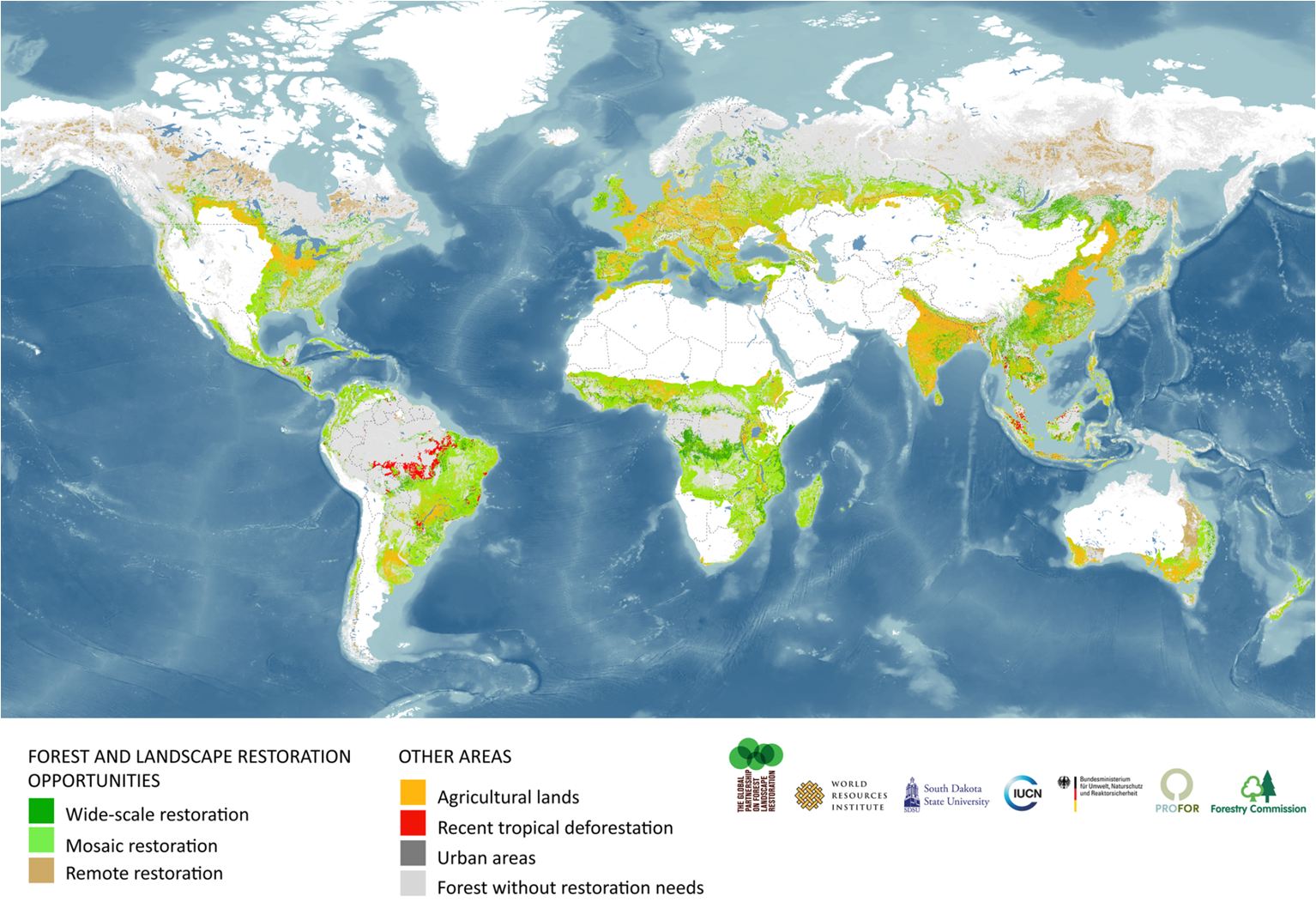

The Atlas of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities—created by WRI, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the University of Maryland—is a coarse-scale map of the possible scale of forest landscape restoration opportunities globally. We created it to inspire and inform restoration initiatives like the Bonn Challenge and to indicate lands where a more refined analysis could be warranted.

How was the Atlas made?

To find opportunities for restoration, we contrasted two global maps—one showing potential natural tree cover and another showing actual tree cover—using pre-existing, globally consistent, geospatial datasets at a 1-kilometer resolution. Potential forest cover was mapped in three density classes based an analysis of climate, soils and ecoregions. A difference between potential and actual tree cover density was taken as an indication of restoration opportunity. All lands with the biophysical capacity to support a tree canopy cover of at least 10 percent were included. This is a broad definition of “forest landscapes” that includes savanna regions with some tree cover. You can read more about the methodology here.

What does the Atlas show?

The Atlas highlights whole landscapes, rather than individual sites, that may offer opportunities for restoration. About one-quarter of these landscapes have the low human population density and biological capacity needed to restore landscapes to dense forest. The majority of restoration opportunity lands might be suitable for what we term “mosaic restoration,” where trees could be integrated with existing land uses, including small-holder cropping and grazing.

How should the Atlas be used?

The Atlas has already inspired and informed the Bonn Challenge and the restoration components of the New York Declaration on Forests. Governments, NGOs and other forest stakeholders have used it to consider their restoration commitments.

Because the Atlas builds on coarse datasets, it does not show exactly where restoration should occur or what restoration activities or interventions are most suitable for a specific location. Rather, the Atlas can be used to guide more detailed analyses in areas highlighted as potentially offering restoration opportunities. Such analyses should consider local ecological conditions, engage local experts and stakeholders, use local forest definitions and incorporate the richer, higher-resolution data sets that are typically available at the country or regional level.

How can people conduct more detailed analyses to support restoration at the local level?

WRI and IUCN developed a Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM) to help stakeholders determine what restoration activities are the most ecologically, socially and economically beneficial in a particular area of degraded land, to understand the social, legal and institutional context that will best enable restoration, and to formulate strategies for moving forward at the national or sub-national level. A ROAM assessment handbook is currently available in a “road test” edition in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese. Governments and non-governmental actors in several countries including Ghana, Rwanda, Mexico, Brazil, Ethiopia, and Kenya have already begun fine-grained restoration opportunity assessments.

What are the next steps in restoration mapping?

There is budding interest from diverse groups to refine the global map and link it with other emerging maps of forest and other ecosystems that are candidates for restoration. Dryland stakeholders wish to capture restoration opportunities in areas with sparse tree cover, such as the African Sahel. Grassland experts want to map old-growth grasslands where tree cover is naturally low and should not be increased through afforestation. The climate mitigation community wants to know how much carbon can be stored in forest landscapes through FLR. Merging those efforts would strengthen the case for restoring degraded lands toward productive use for people and nature.

New products and systems also need to be developed. The Bonn Challenge and the New York Declaration on Forests need a global baseline map against which to monitor progress. Countries that commit to restore need to make national baseline maps and put in place monitoring systems that are sensitive to tree recovery and other aspects of FLR.

We invite researchers and others to collaborate on a more in-depth mapping and monitoring of forest landscapes and their restoration opportunities – at the global, national, or subnational levels - to incorporate new information as it becomes available.

This blog was co-written by Lars Laestadius, Senior Associate at the World Resources Institute, and Katie Reytar, Research Associate at the World Resources Institute.