The Kawésqar legacy

With governance diversity a key theme in conservation, our inspiring person this month is Carolina Huenucoy, the President of the Kawésqar community of Puerto Eden in patagonian Chile. Read our interview where she talks about to Jennifer Kelleher about their community conservation.

Kawésqar communities in Chile have protected their environment for centuries

Photo: Leopoldo Pizarro

In December 2009, the Kawésqar Community was designated a Living Human Treasure by UNESCO, awarded to individuals and communities that are the bearers of tradition or expressions of cultural heritage that are in danger of disappearing.

Q: Can you tell me about your community, where your territory is and a bit about your culture?

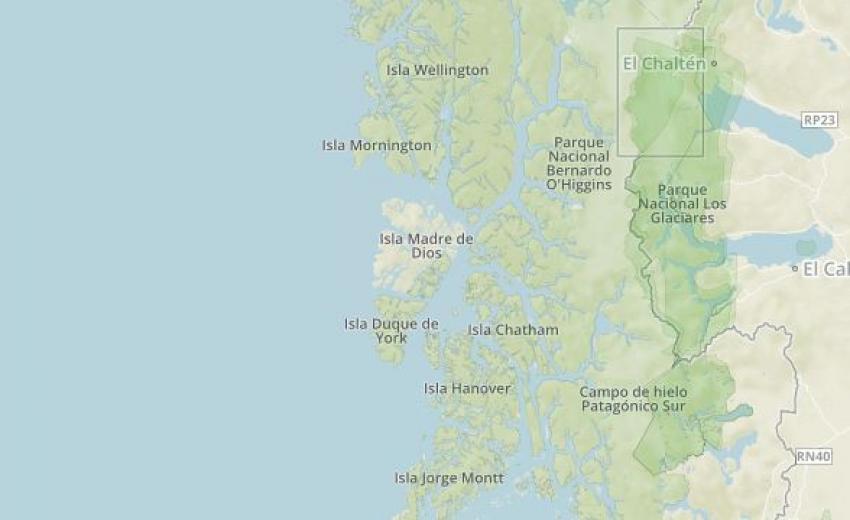

We are a very small community, 25 people including our eight elders. The Kawésqar or sea-nomad territory encompasses the area between the entrance of the Gulf of Penas and the Island Diego de Almagro, a space which has entirely been defined by the elders. For us, ‘Kawésqar culture’ is our territory, our community and our wealth. In this immense space thousands of Kawésqars were born, have grown up, they have lived and died. This cultural wealth exists and lives on in the memory of our eight elders. These elders are passionate to pass on their knowledge to the next generation.

Photo: Jennifer Kelleher/IUCN

Photo: Jennifer Kelleher/IUCN

Q: Can you describe the natural resources that are found there and the importance of those to your community?

It is such a large area that there are many different types of marine species: whales, orcas, fish, and sea lions for example, and we are the only indigenous community that has a quota to hunt sea lions. We also hunt birds, certain types of deer, and we collect and forage wild fruit and plants from the forest. We collect wood for building our boats. We use some plants for medicine, we know that the fibres of certain plants are good for specific uses, however, unfortunately and sadly, medicine is a knowledge that we have mostly lost.

Q. Can you describe the way that your community conserves nature?

Everyone in the community practices nomadic hunting and gathering; we know the places where animals breed and nurse, the areas where we can hunt, fish and harvest. We also use raw materials from the forest to produce our crafts, but we do it in a way that doesn’t damage nature. We take a small and limited amount, just what we need. We take what we know is just and right to take, and no more so that we don’t damage the forest. We also have places that we refer to as taboo places, we call them 'æjamas'. These are the places that we don’t disturb because they have a completely different morphology than the other parts of the territory. The elders say that if you sail close to them, or if you even look at them, the weather will worsen and that hunting will be scarce. So we don’t touch the æjamas, because these are the most important areas to us and are the ones that are strictly protected. We also have the huemul deer here; this is specific type of deer that is native and also endangered. This means that they cannot be hunted and they are protected by law.

Photo: WCMC

Photo: WCMC

Q: Can you tell me about the official protected areas nearby?

It is a huge territory and it is all protected, politically I mean. We have here the Parque Nacional Bernardo O’Higgins and Parque Nacional Torres del Paine. The state protects these areas and all of the flora and fauna here, unfortunately more than they protect the people. The huemules for example in this region have been registered. The state carried out a census of those deer, and registered 88 in one area I believe.

The state uses a huge amount of resources to protect these areas and the species within. We, however, a community of 25 people, are not protected. To us this is the paradox of protected areas. We have been protecting this area with all of its flora and fauna for over 6,000 years. In fact our elders demarcated, defined and named the territory and this territory would not exist without the presence of our people.

Q. You spoke earlier about developing a technological centre, can you please talk a bit about that?

The greatest support that we have received so far has been by the scientific and academic world. Although the practices and memory of our community is oral, it was necessary to capture that oral history and to make it tangible, and the way that that was possible was through science and scientific knowledge. We have a project in mind for which we are searching for resources, a plan to build a technological centre and a lodge. The focus of the technological centre is to invite national and international universities and research centres to work and collaborate with us, to come and conduct research in our territory, because this is the only way we have of protecting this vast territory that we have protected for so long. This will help to support our culture and endorse our presence.

Photo: Leopoldo Pizarro

Photo: Leopoldo Pizarro

Q: What is most important for your community, what message would you like to send out?

The first message is for the state of Chile: we want to say that Chile is indebted to the Indigenous People of Chile. We know and understand that protected areas are a matter for the state, but the decisions that they take to protect these places also need to include local communities and the indigenous people of these areas. That is because protected areas are indigenous territories, they were established inside indigenous territories. Chile has to acknowledge, as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples has, that the indigenous people are the key protagonists in the protection of these territories.

My message to the world? We want to say that the Kawésqar people are alive, we are here and we exist. Our culture and our history is so precious, it is now in the minds and hands of eight elders, and when an elder dies, a part of our history dies along with them. It is a community that needs to be made visible, to be protected and to be shown to the world. And we would also like to invite the scientific community to work together with us. The elders don’t want the knowledge that they have to die with them. They want to pass on this information to all Kawésqar - the ones here now and the ones that are yet to come - but also pass it onto to the world and to all of humanity so that it will not be lost.

Interview by Jennifer Kelleher of the IUCN Global Protected Areas Programme at IMPAC 4, La Serena, Chile, with translation assistance by Elena Pérez (IUCN World Heritage Programme).