Grass-fed livestock is one answer to climate change, not one of the problems

A new study, headed by Pablo Manzano from the IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management, shows that greenhouse gas emissions in pastoralist systems will not differ from natural emissions by wild herbivores. Methodologies that account for livestock emissions should take into account such factors when differentiating across livestock management types.

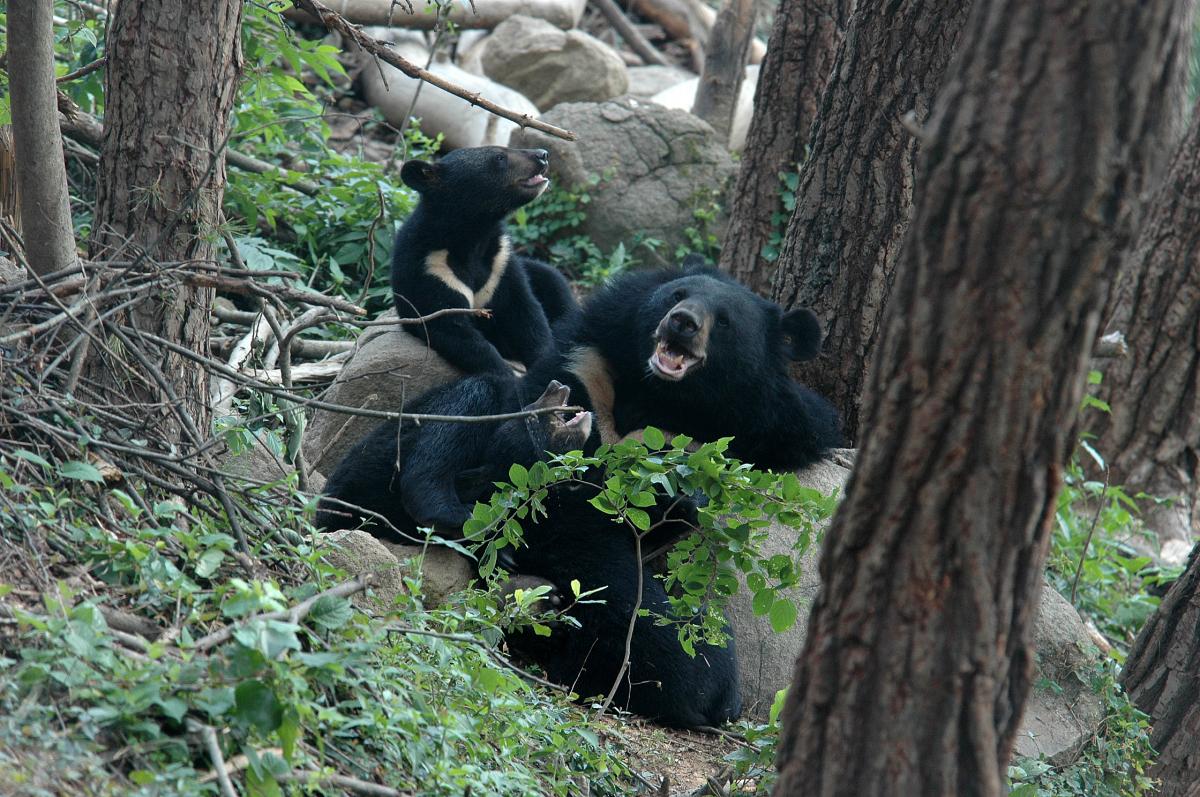

Photo: Ia Ebralidze

In the last years, livestock has been considered one of the greatest threats to climate change, accounting for 14.5 % of estimates for anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Of high concern have been grass-fed systems, as a higher fiber content in livestock diet results in higher methane and nitrogen oxide emissions. Policy recommendations have therefore been oriented towards increasing grain and concentrate content in the livestock diet, as well as replacing ruminants (cattle, sheep, goats) with poultry or pigs.

Pastoralism is a widely distributed livelihood whose value for sustainable community-based management of natural resources has been recognized for long, with dedicated initiatives at IUCN including the World Initative for Sustainable Pastoralism or from IUCN’s Commissions on Ecosystem Management and on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy. It promotes the coexistence of humans and biodiversity, prevents a number of degradation processes and provides livelihoods in the world’s harshest landscapes. However, current accounting of livestock emissions attribute the highest burden to such systems, because they rely on the world’s marginal lands where fibrous fodder is abundant: drylands, mountains and cold areas. The sustainability of the pastoralist practice has been therefore at stake in the last years.

A new study, headed by Pablo Manzano from the IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management, introduces a yet ignored ecosystem perspective to evaluate livestock emissions. Because pastoralist livestock integrates into the grazing ecosystems it occupies, its emissions have to be compared with the ones caused by wild animals in an abandonment scenario. Existing data on wild mammal herbivores in North America or Siberia, as well as termites in the world’s tropics, indicate that a pastoralism scenario will not cause higher greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate policies that weaken pastoralist livelihoods are likely to be very ineffective. The low fodder and transport needs of pastoralist animals translate into a very low need for fossil fuel use. Additionally, any policy damaging pastoralism is likely to have dire consequences on biodiversity and development of the most remote areas. A better knowledge and protection of pastoralist systems, including specific labeling of pastoralism products, is therefore important to achieve sustainability.

Mitigation actions within the pastoralist system that translate also into increased welfare of pastoralists are possible, such as the use of manure-fed cooking stoves that provide homestead energy while reducing methane emissions. Such measures should nevertheless follow a ‘no-harm’ policy of pastoralism to protect the role it has in the world’s grazing ecosystems.