Governance Diversity for Belize

Based on the PARKS 23.1 paper A Governance Spectrum: Protected Areas in Belize.

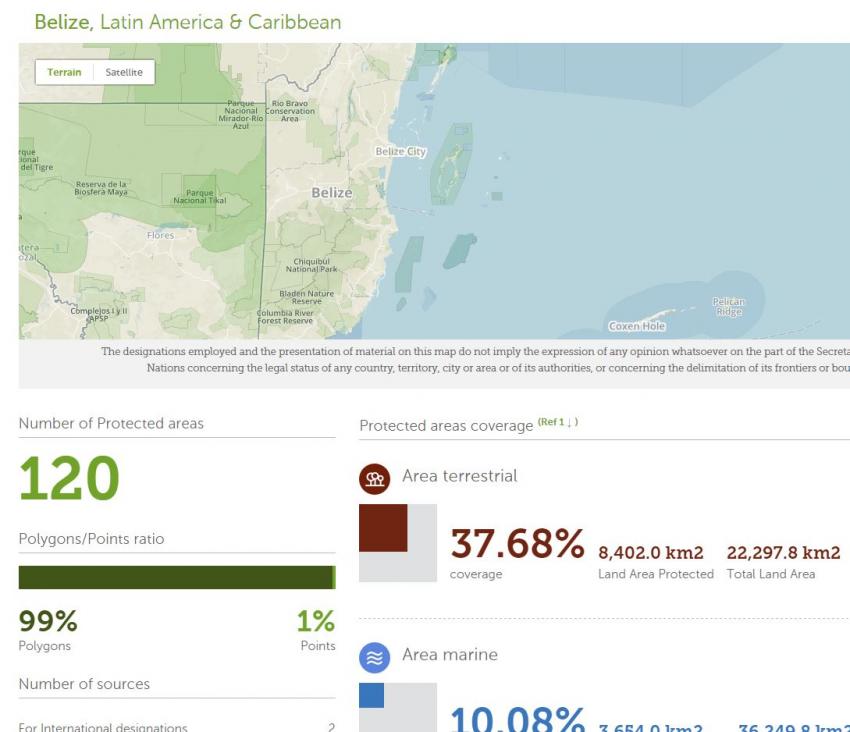

Belize is one of the smallest non-island states in the Americas, but a leader in protected areas designation and governance. Belize is one of only a dozen countries that have met Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 of the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) to conserve 17% of its terrestrial and 10% of its marine areas. Belize manages 36.6% of its terrestrial area in protected areas and 19.8% of its marine area. The size, scale and diversity of protected areas in Belize provide an informative case study of system management and governance that can offer a model for countries with expanding systems.

Belize has three distinct physiographic regions: the flat northern lowlands consisting primarily of limestone and sandy soils, with a complex mosaic of lowland, semi-deciduous forests, savannahs, freshwater rivers and wetlands, with saltwater lagoons and mangroves along the coast; the southern coastal plain with its extensive sandy and rich alluvial soils supporting tropical pine and broadleaf forest; and the Maya Mountains of granite, quartzite, and shales. Within these broad categories 68 ecosystems have been identified. The marine environment supports the second largest coral reef in the world.

Reduced forest connectivity is impacting the viability of large-ranging species such as white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), tourism infrastructure is rapidly removing littoral forest and coastline vegetation, and the increasing number of fishers and level of transboundary incursions are resulting in unsustainable levels of fishing.

Belize’s National Protected Areas System (BNPS) is characterised by a heavy reliance on co-management partnerships, privately protected areas and ICCAs, in that order.

The 2015 National Protected Areas Act replaces the National Park Act of 1981, presenting an updated framework for the System, articulating 13 categories of protected area and consolidating authorities under the Protected Areas Conservation Trust. The Act also establishes the National Protected Areas Advisory Council. Unlike the Protected Areas Conservation Trust, the Council is, with one exception, constituted of government officials. Though criticized for a lack of consultation, the Act significantly strengthens the System by:

- Integrating the legal requirement for stakeholder and community consultation and participation in the designation or revoking of protected areas, and the use of a standardised management planning process;

- Providing a legal framework for integrating privately protected areas (PPAs) into the NPAS;

- Facilitating the provision of “special management areas” for sites outside of the NPAS where critical management actions need to be put in place (for example, in the formation of corridors, or in managing the increasing watercraft activity on the Belize River delta, linked to increasing manatee mortality in this key manatee site);

- Recognising traditional use rights in areas where conflict exists between traditional use and the non- extractive designation of the protected area—if managed under an approved sustainable use management plan.

The greatest weakness in the NPAS has, in the past, been ministerial discretion. Legally, the Minister responsible for protected areas has the power to de-gazette a protected area with the stroke of a pen. This diversity of governance also helps to counteract the issues confronting system management, including: lack of human capital and financial resources; dependence on external funding; and flaws in the taxation system creating perverse incentives to clear land.

The Government of Belize is limited financially, and does not prioritise investment in the NPAS, despite this being the foundation for its tourism industry. It therefore relies heavily on its co-management partners (and increasingly PPAs and ICCAs) for locating the financial resources required for effective management. However, such assistance from civil society can lead to an abdication by government of its role in managing protected areas, and lead to an under-appreciation of the value of the National Protected Areas System — not only by government, but also by the Belizean people.

Article by Brent A. Mitchell, based on A Governance Spectrum: Protected Areas in Belize by Brent A. Mitchell, Zoe Walker and Paul Walker in PARKS Journal 23.1 2017

- Belize on Protected Planet

- See the full list of papers in PARKS 23.1

- Visit IUCN Global Protected Areas Programme governance site