Our Red List Species Assessors: Keeping up to speed with snails and slugs, an interview with Ben Rowson

Terrestrial molluscs, which include snails and slugs, are prey to a large variety of animals, and provide important ecological functions such as soil and compost formation. In this interview with Dr Ben Rowson, a terrestrial mollusc expert based in Cardiff, Wales, he talks about his work and involvement with terrestrial mollusc research and conservation.

This is the third of a series of interviews with our Red List Species Assessors currently involved in IUCN’s European Red Lists LIFE project. Our interviewee is a terrestrial mollusc expert, but future interviews will profile beetle, moss, fern, and other plant experts. The project aims to assess the extinction risk of these species groups, and will contribute to guiding policy decisions and conservation actions at the European level. Read past interviews of this series here and here.

Dr Rowson’s interest in invertebrates was piqued at a young age. “I became a keen natural history person from an early age and didn’t grow out of it. I was particularly fascinated by shells as a kid, their form and variety. It becomes immediately obvious that some are very common and you can find them all over the place, whereas others are much rarer.”

Dr Rowson studied Entomology at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, and later did his PhD at Cardiff University on tropical carnivorous snails. His studies led to his job as Curator of terrestrial molluscs at the Department of Natural Sciences of the National Museum of Wales. “Slugs and snails are closely related to one another, as slugs are actually a highly advanced and evolved type of snail. There are slugs and snails all over the world and in all environments from deserts to high mountain tops. Because they are slow moving they tend to be restricted to small areas, sometimes just a few square kilometres and for that reason there are a lot of endemic species.”

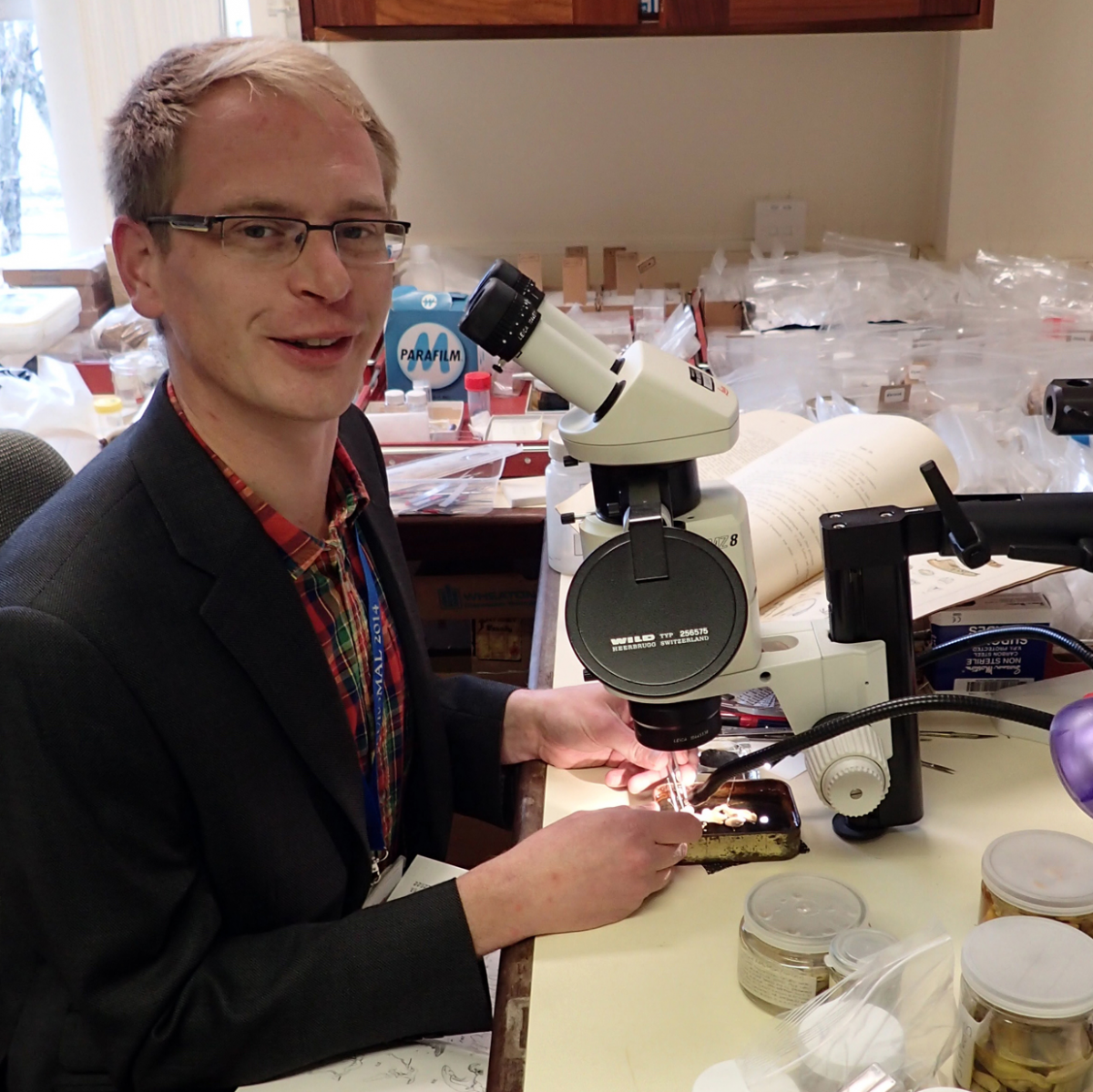

Photo: Ben Rowson

Photo: Ben Rowson

Museum researchers with access to vast collections of terrestrial molluscs from all around the world have a critical role to play in increasing our knowledge about this group and in describing new species to science. They can also work to increase capacity in developing countries. “My predecessor at the museum, Mary Seddon, was involved in setting up a project involving capacity building in East Africa, where we used the mollusc collections here in the UK to develop better skills in East African countries like Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda and to help those countries understand their biodiversity better.”

Terrestrial molluscs vary enormously in size, from large African carnivorous snails to species you would need a microscope to see, and field work methods depend on the size of your target species. “Terrestrial molluscs are not the most difficult thing to catch, but finding their exact microhabitat can be very challenging. Many species are extremely small - you might need to use special techniques to get them. For example, by collecting the leaf litter of a shady forest and then running that through a series of sieves you would be able to find the tiniest snails. On the other hand, some of them are large enough that you can find them easily with a torch at night or by setting up traps.”

Snails and slugs have important functions such as soil and compost formation and are also prey to a large variety of animals, from other invertebrates to birds and mammals. Dr Ben Rowson is currently assessing the extinction risk of a selection of British and Irish slugs as part of the LIFE project, which is assessing the extinction risk of all European terrestrial molluscs. “Generally speaking, many species are found in undisturbed habitats. Places like old forests, unimproved grasslands and large undrained wetlands. Anything that has a major impact on those habitats will kill molluscs by the millions. They are not necessarily rare in terms of numbers, but they are often restricted in their distribution and habitat. They are also threatened by the use of molluscicides and by invasive species, which can compete with them and take over their habitat, making the native species rarer.”

Photo: Ben Rowson

Photo: Ben Rowson

According to Dr Rowson, there is still a huge knowledge deficit about the threats facing terrestrial molluscs and the potential options to mitigate those threats. Some species have declined or disappeared from large areas and the reasons for their disappearance remain unknown. “The Heath Snail (Helicella itala) used to be very common in short grassland, but has become much less common over the 20th Century and it is very difficult to find now. No one is really sure why.”

Other terrestrial molluscs are only known to us from specimens in museums, and a shell can be all that is left of a snail species. “More molluscs have gone extinct in historic times than mammals, birds and reptiles put together – which is why the first thing you need is to have a decent inventory of what species are out there and to know to what extent they are threatened, such as the IUCN European Red List of Threatened Species. The good news is that many invertebrates will respond well to measures taken to help protect their habitats.”

As for Dr Rowson’s favourite terrestrial mollusc: “Arianta arbustorum – it is not a rare species, but has an attractive shell which looks like polished wood, and it reminds me of the pews of the church where I used to go when I was a kid.”